Hello and happy near-end-of-the week to you. A brief update:

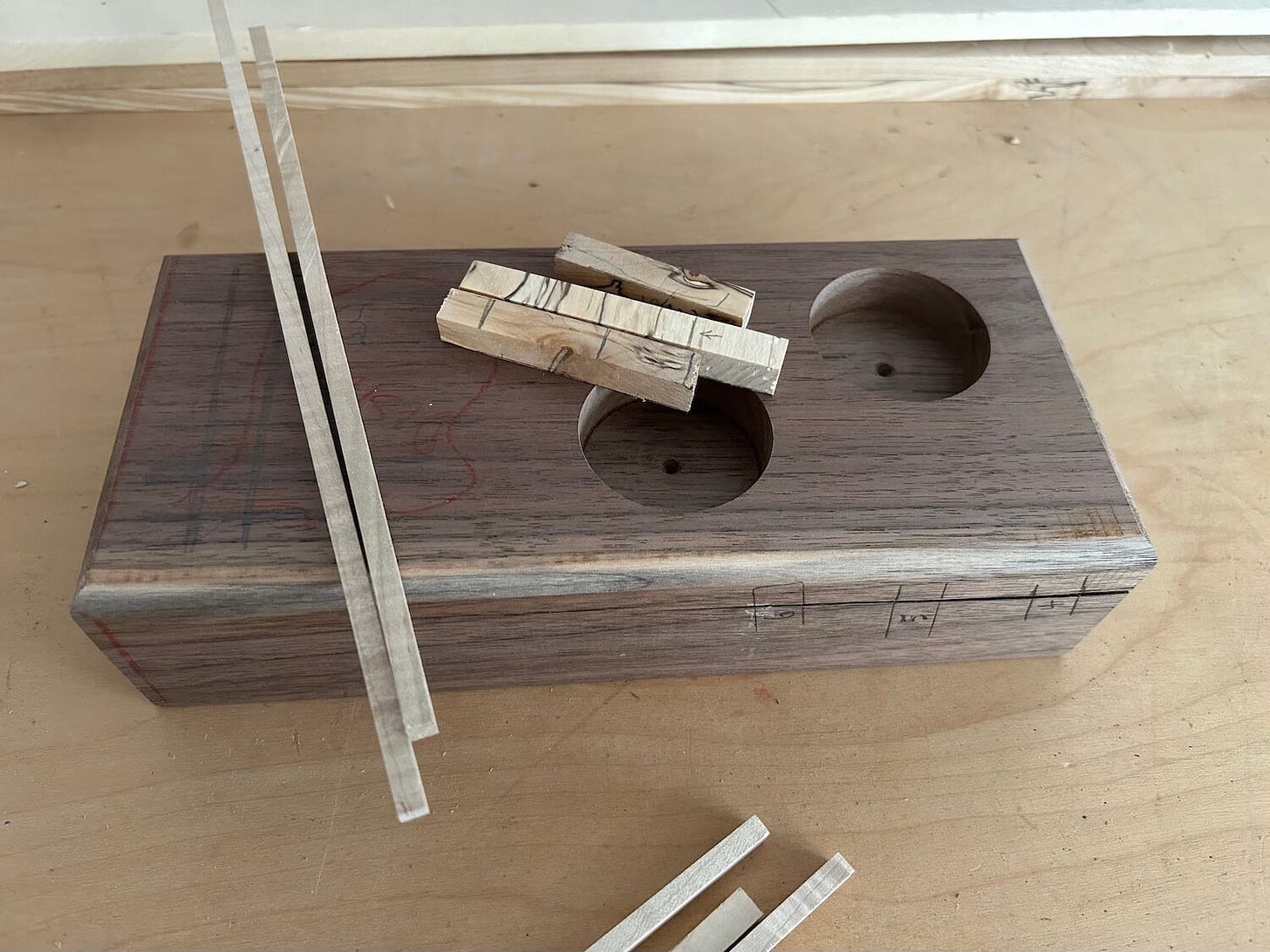

My new shop is done—the garage has been converted to a space that is insulated, warm, and somewhat lit. I’ve yet to put up my other two lights or my air filtration system. I need to get my table saw on the mobile base. And I think I’ve got to move some of the equipment around to make the work flow better. But at least it’s a cozy space that is all mine. It feels quite decadent.

I’ve been reading the tenth anniversary of Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains and thinking a lot about this little newsletter and my own writing on the internet. Upon bringing some of these thoughts to my pragmatic partner, Josiah told me I was overthinking it. Part of me wonders if 15 years isn’t long enough to really get to know someone because overthinking things is what I do. He should know this by now.

My essay is below. I hope the next couple of weeks find you unearthing powerful wisdom. Or at least excavating some mental trenches and clearing up space for new insights!

(Some of) What I'm talking about when I talk about woodworking

Woodworking is less about the thing being created than the act of creation. As much as I love finishing projects and seeing stuff I’ve made become real in the world, I’ve begun to realize I’m not much of an end result kind of person.

I’ve just finished writing a grant application to fund a project—an exploration of craft as medicine, of the benefits people get by working with their hands. This project is a big swing for me; it’d involve working with several other artists, putting together an exhibition, and presenting these ideas to the public next spring. I was talking to a friend about this recently and she asked me, if I get the funding, could I imagine how I might feel the day after this whole project has been completed and the exhibition is finally done? I responded that I’d feel neutral. Not relief, not joy, not a sense of accomplishment. I’d be on to whatever I was working on that day, the finished project slipped into my mental archives.

And I think that’s what draws me to woodworking. If the end result is what matters most, working by hand is probably the worst way to get there. Working by hand is all about the process, the many meandering steps toward the destination.

As an example: In woodworking, you have to take account of wood movement. Wood is not a static material. When the air around it gets warm and humid, the pores in the grain swell and the wood increases in size. When the air gets cold and dry, that same grain retracts, the water escaping back into the air, the wood shrinking in response.

Wood reacts to its environment. The poet in me (such as there is) wants to wax on about the aliveness of wood. The woodworker in me just wants to make something that doesn’t crack apart when the season changes. Holding the tension between the two—the artist, say, and the craftsperson focused on earning some money—that’s one of the things I’m talking about when I talk about woodworking.

Woodworking, done well, is really the art of getting out of your own way. At every step of a project, I’m reminded of this, from design to joinery to finish. Just like cat skinning, there is generally more than one way to do most of these tasks. Too often I find myself dithering over what might be the best way to go about the work when really the best way would be just to begin.

This is also true of the material itself, the wood, the pearl or silver or beads I’m using for inlay, the forms I’m cutting in my scroll saw. The point isn’t to do all of it, dressing it up like a gaudy salesman of an item that wants to show off all my skills at once. The point is for the life of the material to shine through the design. For the piece to showcase the figure and strength of the wood.

Josiah (my partner and hobby enabler) bought me the book, Drawing on the Right Side of Your Brain. The author, Betty Edwards, writes about how we have to quiet the logical, labeling, verbal part of our brain in order to draw. That part of our brain just wants to verbally dissect everything it sees and to quickly assign stereotypical shapes to what we’re trying to draw and move on to something else, which causes us to draw symbols instead of eyes or noses or flowers or whatever.

I think the same kind of thing happens in woodworking or other creative endeavors. For me, in the shop, it’s about quieting the overbearing chatter that wants to label and critique and dissect every little move. Once I get to that quiet space—what feels to me like getting out of my own way—I’m more open to what’s right in front of me, to highlighting what brought me to this piece of wood in the first place, using my few skills to the best of my aptitude to showcase that to others.

And finally, woodworking, at least how I practice it, is contingent on the kindness of others. Even my solo work in the shop took a collaborative effort to get there.

My dad taught me how to cut up a board, right its edges, how to set up the machines and fix them when needed. How to think about constructing furniture. To listen to the cut. To pay attention when there is deviation in your project. Measure twice and all that. How to slow down.

Others have taught me how they think about design or their approaches to solving the 3D puzzles in various projects. Mark taught me how to inlay materials and hone closely in on the small details that make a project distinct from others. Dave taught me how to turn a hunk of log into a bowl.

Each time I see another woodworker’s creation, I learn. Josiah particularly likes it when I get down on the floor to examine a table or cabinet from all angles. He says it’s downright charming when I do that at dinner parties.

I felt these connections keenly this last week setting up my shop. If it weren’t for Josiah’s ability to lift the sides of heavy equipment and my work bench, nothing would be level in the garage. But even when I was physically alone, the lessons, encouragement, and support from others were woven through every decision, every action.

It’s a ruse to think any of us are self-made, lone operators. It’s denial and it’s an admission of weakness, even if glossed up like strength. I wish it weren’t such a common narrative. How could any one individual possibly be stronger alone? Alone we are wolf meat, a crunchy snack for predators. Together we learn, build, create, develop new future possibilities. Even the frustrating aspects of being in relationships with others, I’d argue, make us better, if for no other reason than they keep us honest about our own shortcomings.

Thanks for being here. What do you think about when you’re working with your hands?

nice work, enjoy the new space. Hope the new home works for yourself and Josiah.

I am a friend of your Dads and he is helping me build a walnut table for my home. He is a wonderful man. And I am learning a lot from him. I like reading your posts and hope we meet some day.